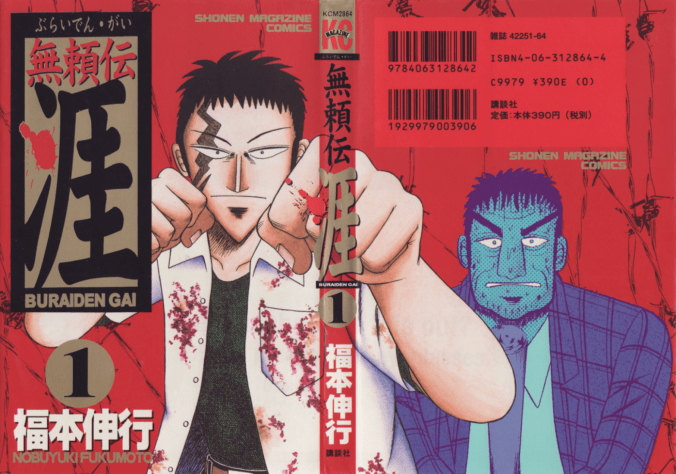

There are many niches in the manga world, and one of the most unique ones is the “mahjong manga”. The monthly magazine Kindai Mahjong by the publishing house Takeshobo first hit the shelves in 1972 as a text magazine, and a manga magazine followed in 1980. Ever since then it has brought many interesting beloved series to the world, and even kickstarted the career of Nobuyuki Fukumoto, who would gain critical and popular success with his two hit series Akagi: Yami ni Oritatta Tensai and Ten: Tenhou-doori no Kaidanji.

Now, the idea of a mahjong magazine seems odd: All the manga that are released here have to feature this game of tiles – something not everyone is familiar with, especially outside Japan. It poses a simple yet deserved question: If everything is centered around a single game that must be the focus, doesn’t it get awfully stale or boring really fast? Surely the authors must be limited in their choice of stories and characters, right?

Surprisingly, this is not the case.

In fact, if one looks at it closer, it gives a lot of freedom. There must be mahjong in it, surely, but the rest can be chosen freely and this has led to some amazing series: Akagi and Ten both combine yakuza and villain plots with deep human drama, Tetsunaki no Kirinji by Uhyosuke is about a divorced single father dealing with his online mahjong addiction to take care of his daughter, Getter Robo High! mixes Go Nagai mecha, mahjong and high school, and Legend of Koizumi by Hideki Oowada is, well, world politics on crack.

If you haven’t seen Legend of Koizumi, I highly recommend that you do.

The best proof of this freedom is that Kindai Mahjong is not only still going after 38 years, but also that it has spawned many spinoff magazines with different readerships. Kindai Mahjong is not one of the biggest magazines out there, but it enjoys its stable cult status and continues its run.

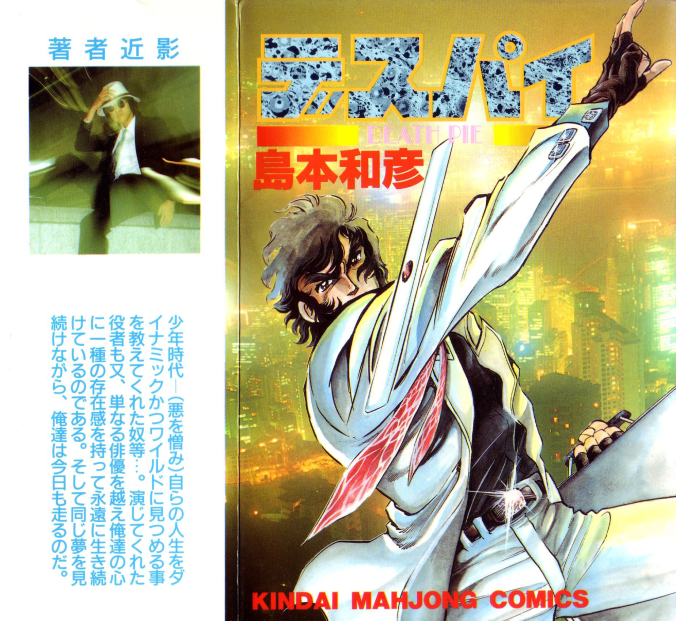

I wish to present one short series from this magazine, to show what is possible within this mahjong frame: Death Pie by Kazuhiko Shimamoto, from 1989.

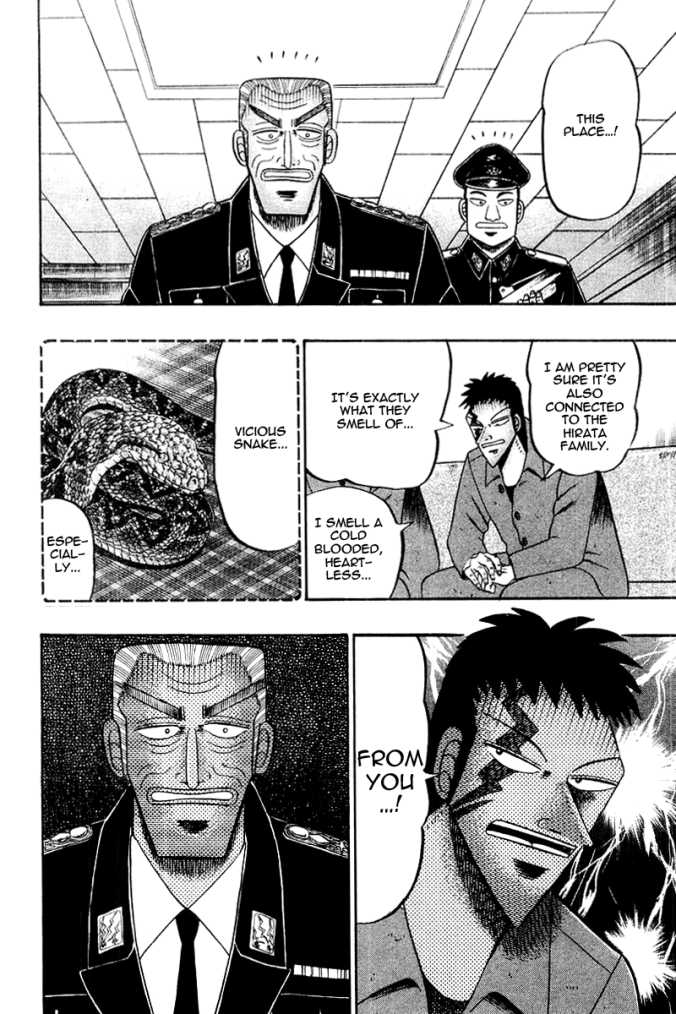

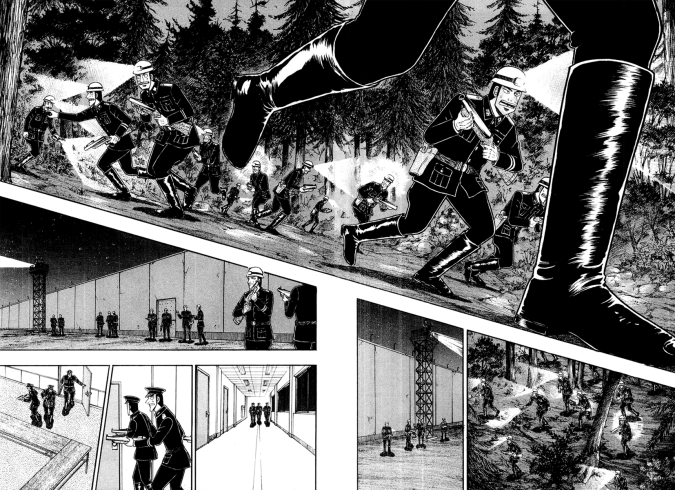

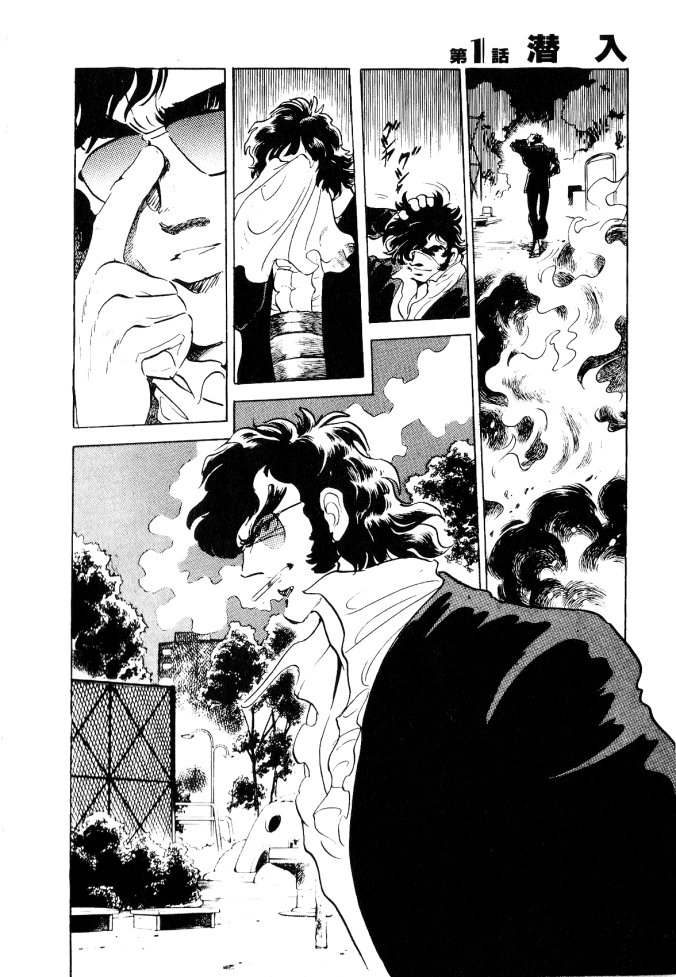

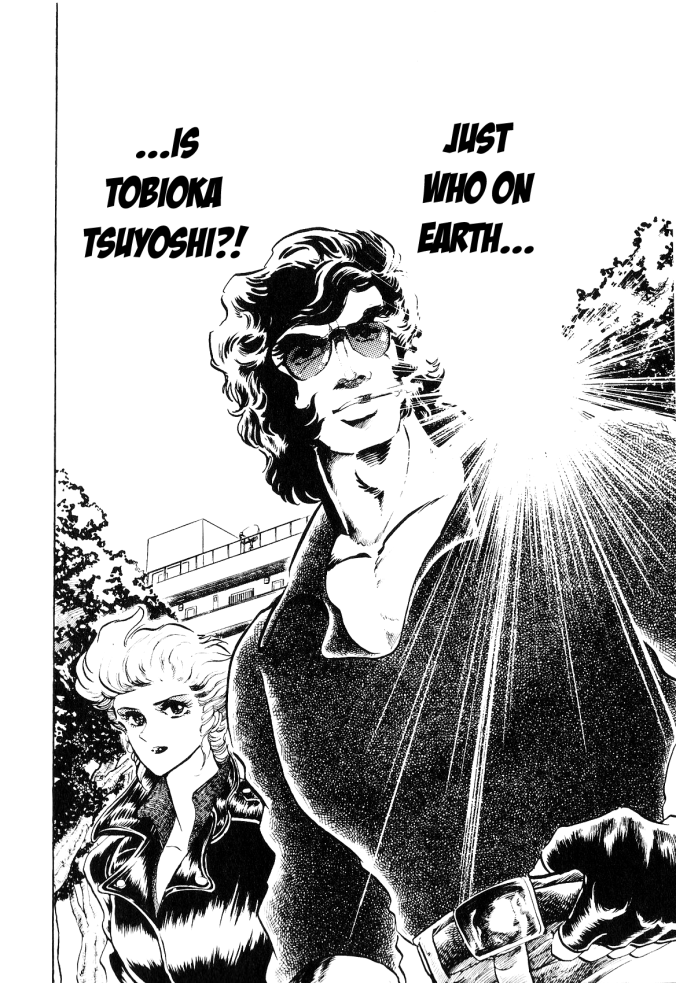

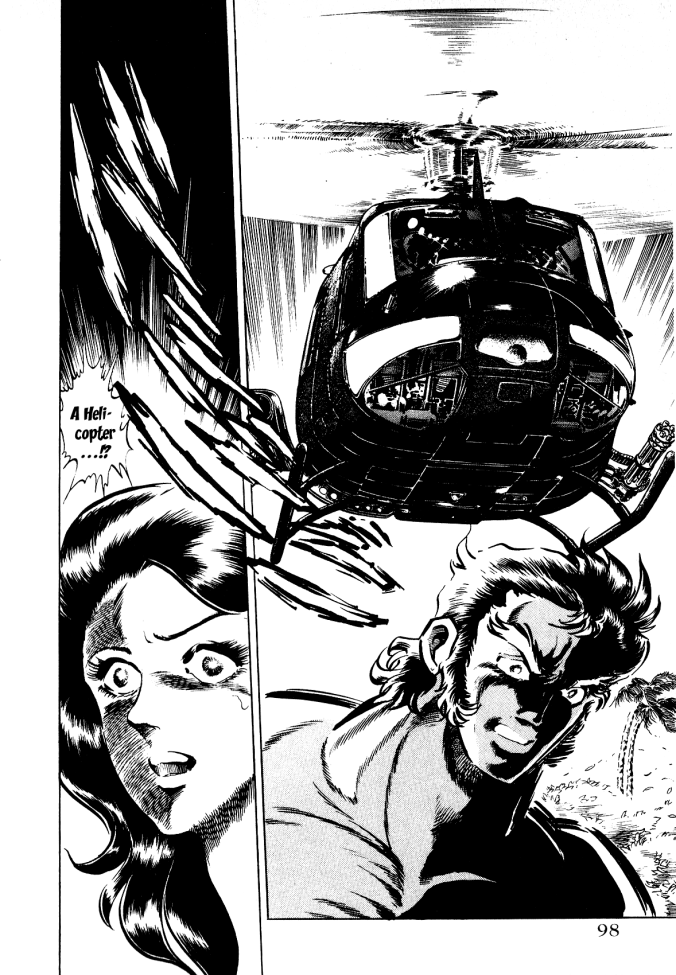

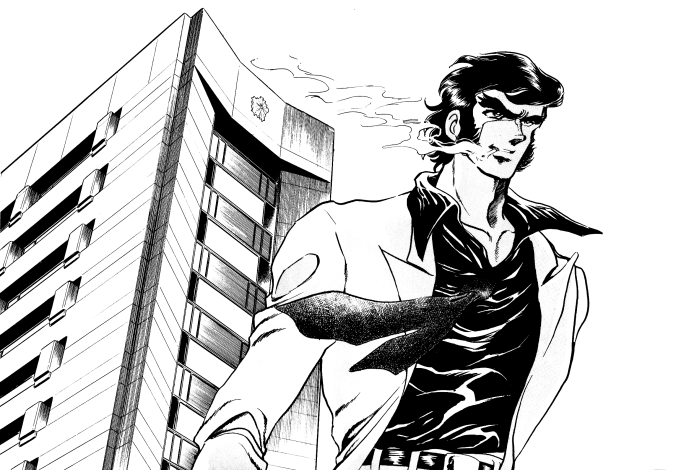

Death Pie is the story of Tobioka Tsuboshi, an ex-cop fighting against drug cartels, who plays mahjong against big yakuza clans and defeats them monetarily. Of course, more plot threads will open: undercover missions, secret infiltrations, backstabbings and fights for life and death with tiles and guns. It feels distinctly “James Bond” in its story beats, but in its look and characters as well:

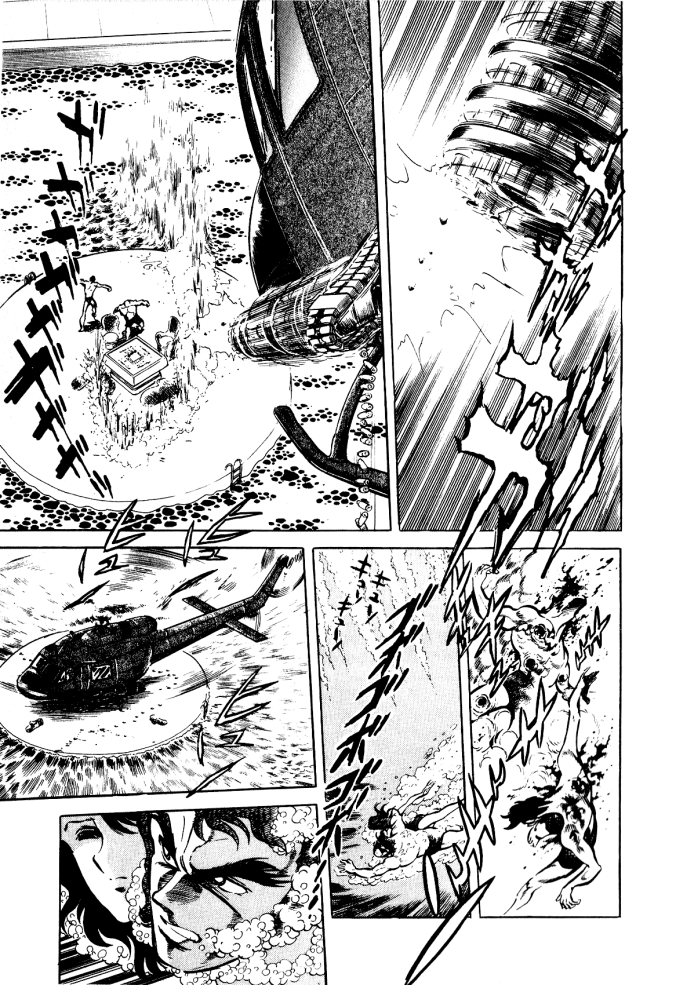

Smooth manly men in suits, good-looking classy women, overly evil villains, capable dangerous henchmen, high stakes gambling, secret casinos, action scenes and explosions in helicopters, cars and ships – everything that simply says “007” is here. Despite its yakuza setting, it borrows the feel of a Western style action film, and it fits.

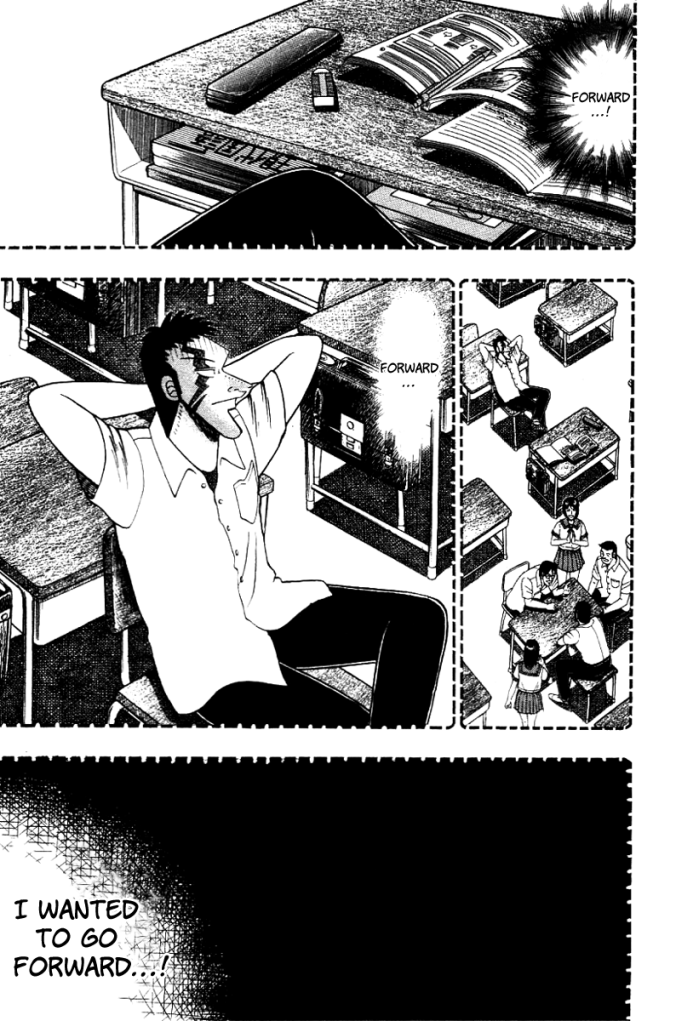

A very rad action protagonist. Who also plays mahjong.

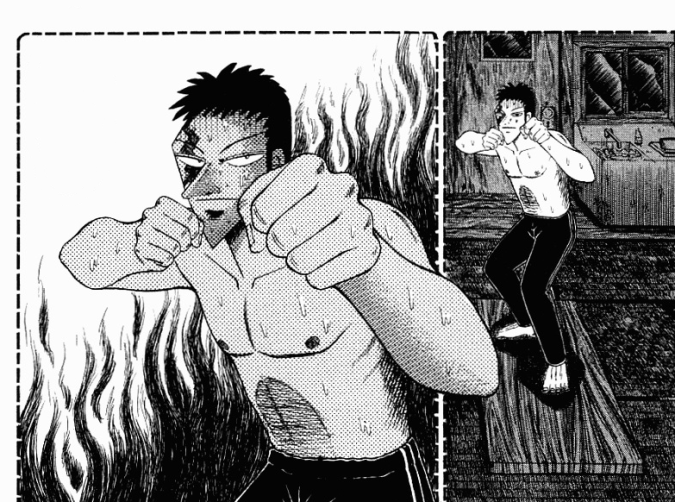

The look of the series brings me to another great quality this manga has: the art by Kazuhiko Shimamoto. He is mostly known for his “Blazing Transfer Student” series, but also other series that feature flames and blazes in the title, such as the autobiographical “Blue Blazes” (which has a fantastic TV adaptation) and “Burning Pen”. “Blazing Transfer Students REBORN” also received a Netflix live action reboot/revival in 2017, which I also highly recommend.

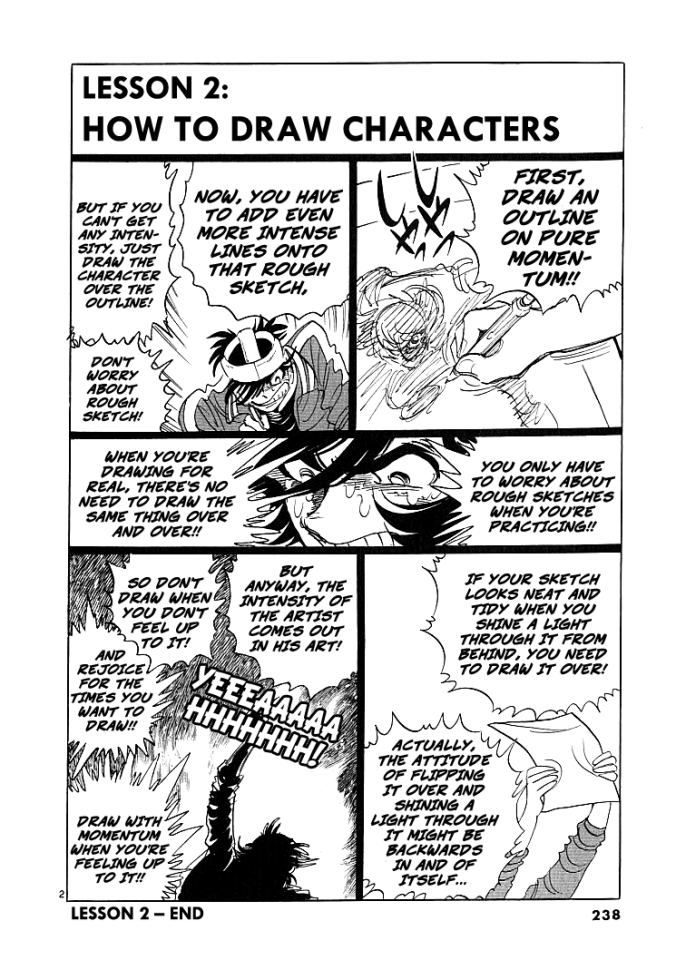

And as you can probably tell from that selection, his series are characterised by BURNING PASSION and HOTBLOODED ACTION. Here you will find big emotions, huge clashes, and energetic characters who will fight for what they believe in. This is reflected in his artstyle, which is drawn with the same amount of power. Shimamoto does not only tell stories with fire, he IS the fire.

Shimamoto explaining HOTBLOODED DRAWING.

In his making-of/behind the scenes manga Burning Pen he describes his approach to drawing: Have the same amount of passion as your characters, and bring that directly onto the paper. And it shows, with heavy contrast, stark brushstrokes modeling his characters, and thick outlines that make objects and sound words come alive.

That’s one way to end a mahjong pool party.

I wish to especially point out the use of ink brushes, especially to draw the male characters hair, which gives everything a great sense of movement. The linework is outstanding, and gives the whole series an immense energetic feel.

Of course, as Death Pie is very short, with only 9 chapters, I do not wish to talk a lot more about the story, and as I already said earlier, the plot feels distinctly James Bond, with the personal touch of Shimamoto.

But how does mahjong fit in with all of this?

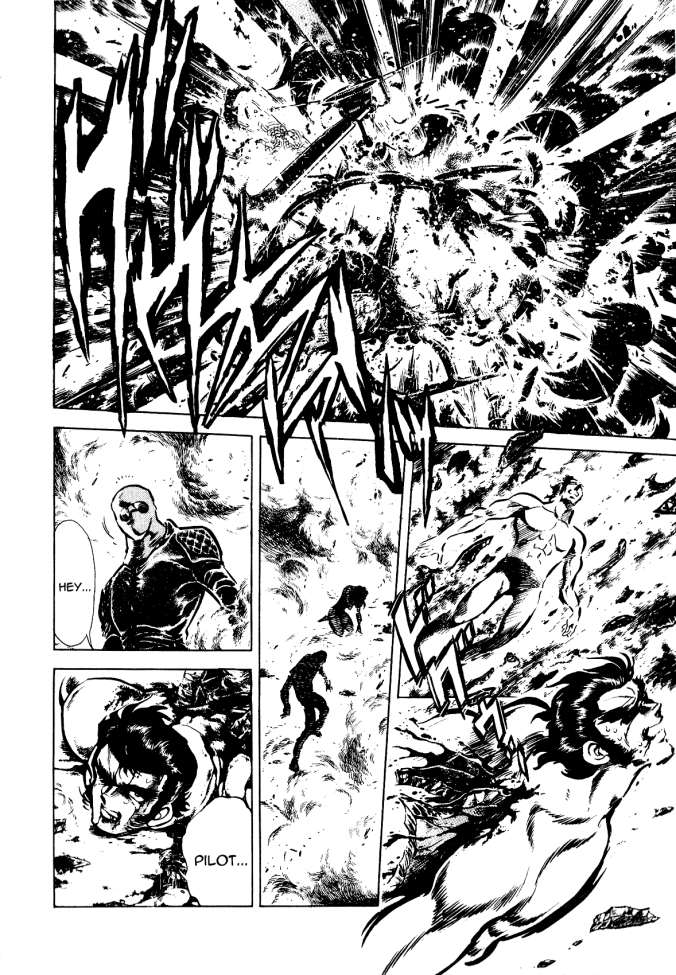

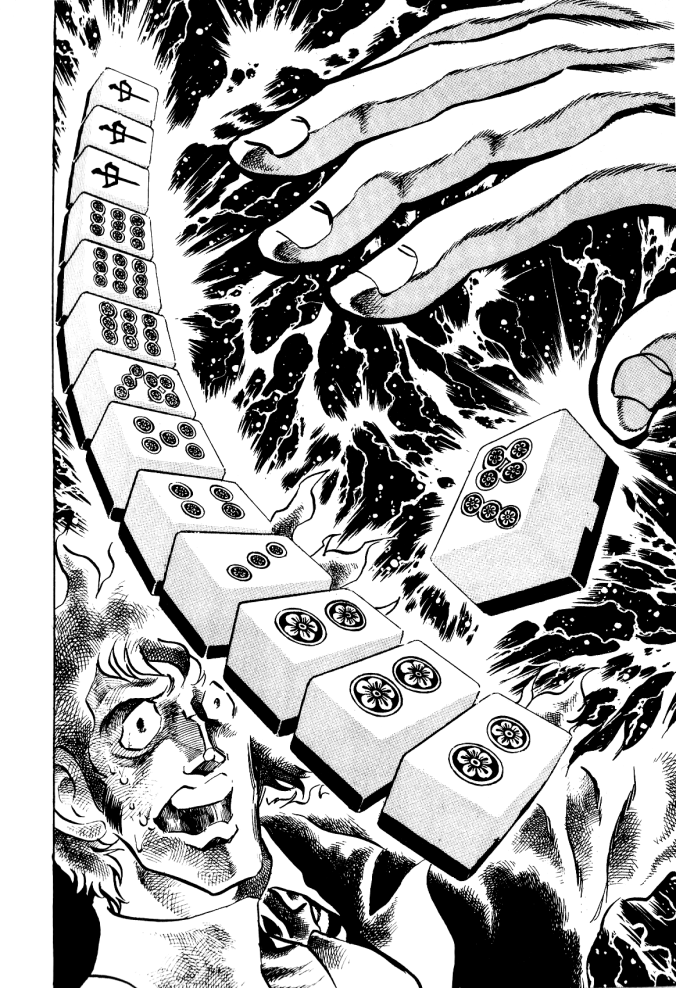

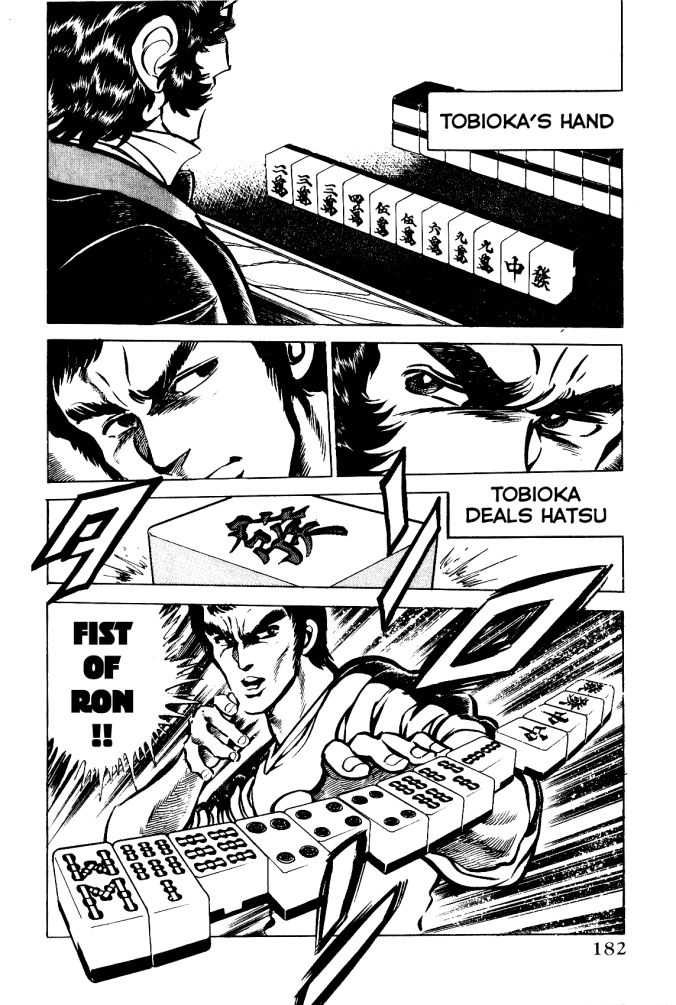

The underworld and gambling go together hand in hand already, and so it does in this story as well. But Shimamoto’s presentation lifts it to another level. Most mahjong manga have intense games with outlandishly gigantic imagery, such as the visual metaphors in Akagi, or the special attacks in Legend of Koizumi, and Shimamoto’s trademark HOTBLOODEDNESS brings it’s own visual look to the table.

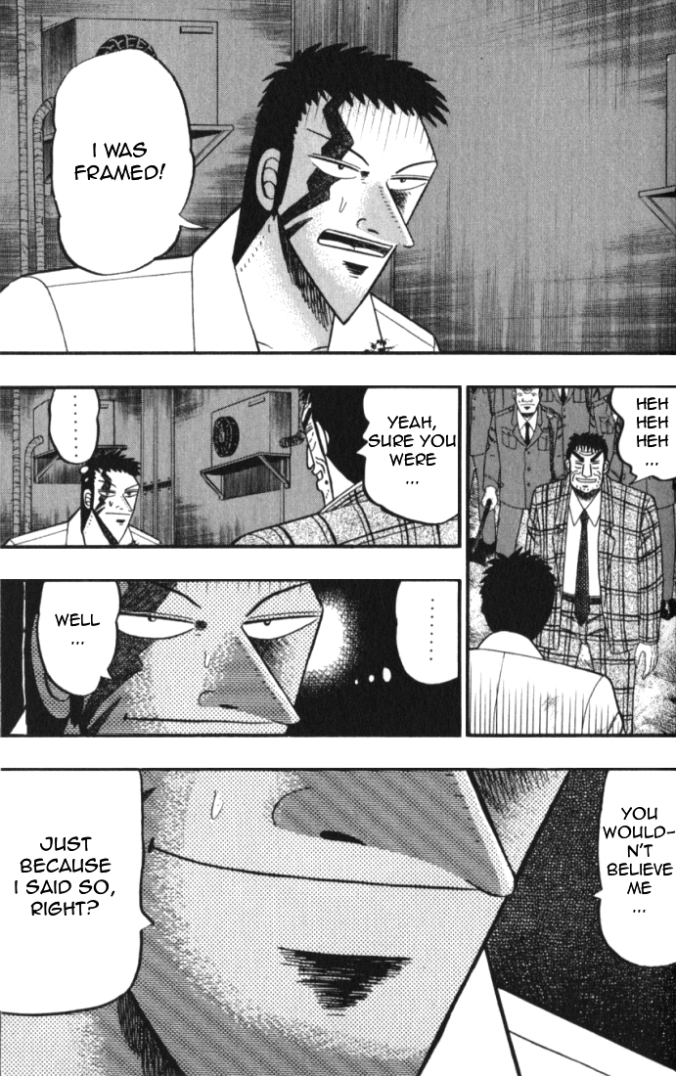

For comparison: Nobuyuki Fukumoto’s Akagi…

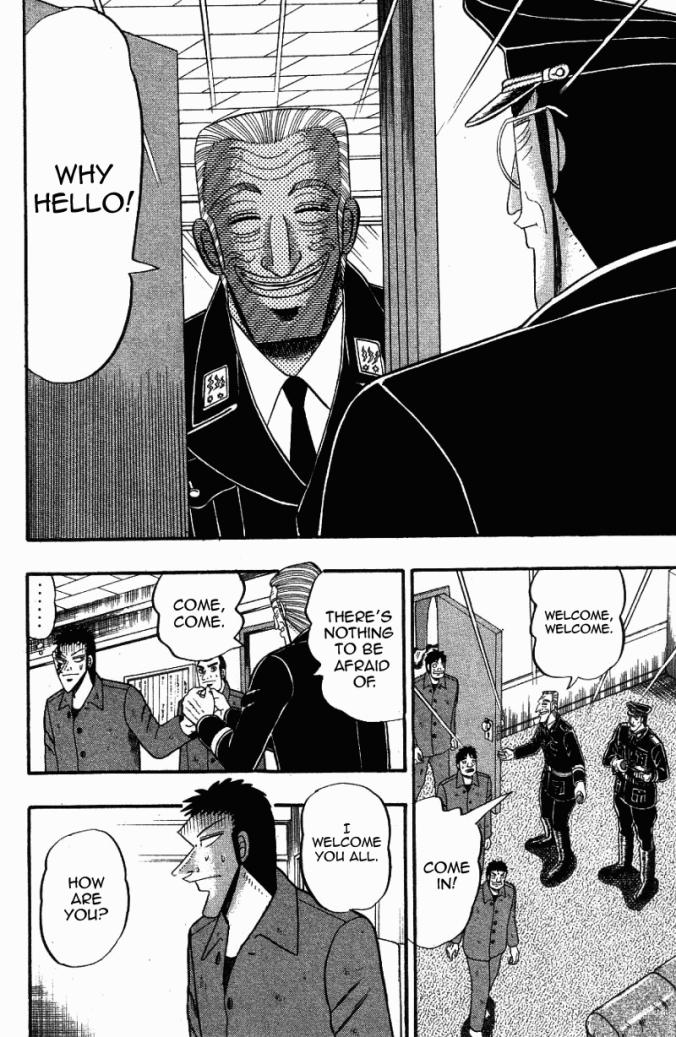

…Hideki Oowada’s Legend of Koizumi…

… and Kazuhiko Shimamoto’s Death Pie.

And for those worrying about not knowing the rules of mahjong, this series does not put an immense focus on it. It is rather the surroundings and settings that make it fun, as well as the villains. The serious action film look with the over the top presentation of the mahjong manga creates a fantastic feeling, that is worth reading this series for. The plot can get a bit convoluted, or you may lose track of some characters, but in the end, it is all worth it: for the artstyle, the character design, the drawings, and the fact that one of the henchmen is Mahjong Bruce Lee.

Death Pie is a little gem that I would like to recommend to everybody. With its very short run of 9 chapters, you can easily read it in an afternoon and enjoy it to your heart’s content.

There will be something for everyone in here, be it the thrill of mahjong, the energetic artstyle, the larger than life characters, or simply the interest to check something out from a decade long past, in a niche manga magazine that has lived for many years and will for many years to come.

The End.

Sources: Wikipedia: Kindai Mahjong, MyAnimeList: Death Pie, Mahjongkrazy Scanlation Notes